(Physical: Pressure)

The Stanthorpe Granite is thought to have formed approximately two or more kilometers underground, beneath a layer of older rock.

|

As the great weight of the older rock sitting above the Stanthorpe Granite was gradually eroded away, immense pressures were released, allowing the upper face of the granite to expand upwards and then crack. These cracks are called "joints". Some of these joints – "sheeting joints" – ran roughly parallel to the land's surface, resulting in large slabs or "sheets" of granite breaking free from the mass below. This process is called "pressure release" or "unloading". The granite sheets may be between one meter to several meters thick.

|

As the granite expanded, vertical joints broke the horizontal sheets into blocks. Subsequent weathering has widened the joints between the blocks and worn away the sharp corners and edges. Over time, the roughly rectangular blocks are converted into accumulations of rounded boulders.

|

Depending on the local fracture patterns, the weathering of the granite occurs at varying rates. Where there are a lot of fractures, the rock is weathered away more easily. These places become valleys with only small boulders.

At Girraween, where the rock seems to be less fractured than elsewhere in the Granite Belt, very large areas are able to resist the weathering and erosive forces. The results are broad slabs, steep domes and pinnacles of bare granite.

Thus, the bald hills with rounded summits and steep slopes that are the most striking granite features in the park (The Pyramids, Castle Rock and Mt Norman), are not discrete bodies, but simply "small", less-fractured parts of the larger, underlying granite mass.

|

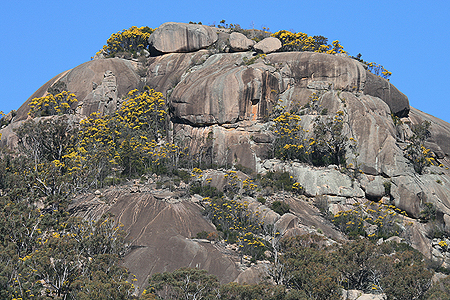

The fractured peak of Castle Rock.

|

Granite domes are sometimes described in texts as "inselbergs", which means "island mountains", but the term is best restricted to domes rising abruptly from flat plains. The granite domes of Girraween are part of a convoluted landscape of hills, ridges and valleys.

Photos...

|

|

Next...

Exfoliation – Rocks that shed their skin.

|