|

|

Tom was the first Overseer of Girraween National Park.

Interviewer: Vanessa Ryan

[The interview was conducted by telephone.]

[So Tom], what's your relationship with the park?

I was the first Overseer there. Took up duty on the 14th of February 1966, which happened to be Decimal Day and Valentine's Day. In those days we weren't called Rangers, we were Overseers.

|

|

|

|

Ok, you've answered my first two questions with that... So, how long did you work in Girraween National Park?

We left there around about Christmas in 1972 - it was just before Christmas. Transferred to Binna Burra.

Ok, we do the math and that's about...

Ah, just coming up six years. Not quite six years. [Not quite seven years.]

Had you ever been to Girraween before you started working there?

Yes. My boss at the time, who was based in Brisbane, Herb Hausknect, took me there some time early January to meet the Gunns, who were the property owners, and have a quick look around. And I must admit, I was wondering what the heck I'd let myself in for when we drove down the hill and I saw that dirty great big boulder sitting up on the horizon. That was my introduction to Girr... Well, it wasn't called Girraween then by the way, it was Bald Rock Creek National Park.

So, it was two parks at that stage, wasn't it?

It was two parks. The transfer of the Gunn property was still going through to link up the two parks.

How did you come about working in Girraween?

Oh, I was a Johnny Come-do-everything... I was sort of all over the place and I was based at Queen Mary Falls at the time. They were starting up Girraween and Herb Hausknect, who was the Forest Ranger, came up and he said "I've got good news for you. You've been transferred to this new national park out near a place called Wyberba". He said, "You can say no, but you're going anyway". That's how I came to go there. 'Cause I'd been all over the place. Ravensbourne, Queen Mary Falls, Mt Glorious... All over the place as sort of a spare parts man, if you like. And they were obviously looking for somebody that was capable of looking after [it]. In those days, we were very independent. We didn't have regular visits from the boss. We were landed there and not even given a works program, or a budget, or anything. We were very independent.

So they wanted good management types? You know, you knew what you had to do and you'd get down and do it?

Absolutely, that's the way it was. I don't know if it was called "management" in those days. It was more development - and I hate that word "development". But that's what was expected of me. To provide facilities for people who wanted to go to, what was then, Bald Rock Creek National Park.

Who were the staff working with you?

The first one was Bill Goebel. I was there a fortnight when I was told that the National Parks Association was sending up a small group of people in September to have a look at the park, ready for a big invasion the following year. And they wanted toilets... And at that time, of course, what's now all the picnic ground - that was all apple orchids. So the first job was to get rid of all those highly productive apple trees and get ready to build some toilets.

|

|

Bill Goebel was put on for, I think it was, eight weeks, but Averil and I were getting married in May, so I virtually had to close the place down while we got married and went on our Honeymoon. After we came back from our Honeymoon, I put Bill back on again and he stayed there until he retired.

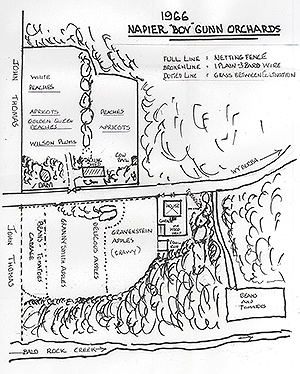

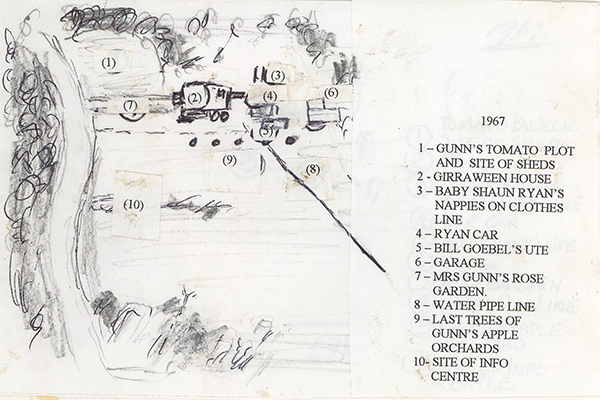

So we got rid of all the apples... The first orchard was up near the house. That was Gravenstein apples and then there was Delicious, Granny Smiths and then right down the bottom there was about an acre of ground that Boy Gunn, or Napier was his proper name - his nickname was Boy - where he grew cauliflowers and cabbages. And then up near the house, where I built that big store shed later on, that's where he grew some tomatoes. So that was the national park, if you like, that I inherited. I think at that time it's fair to say that we weren't the most popular people in the district because it was a highly productive orchard and that was being lost to the Granite Belt. But it didn't take long for people to appreciate what was happening there.

We managed to get that toilet block and the water supply up and running before the end of September when the National Parks people turned up. That was the major introduction, if you like, to the development of Girraween National Park. That's what brought people there.

|

|

Tom's sketch of Gunn's orchards.

|

|

That sort of answers my next question, but I'm sure you can add more to it. What sort of duties did you undertake while you were working in Girraween?

Well, initially for the first few months my whole world was just centred around that orchard - getting that toilet block built.

|

|

As people started to come, we were... I think in those days, the people on the park - that was Averil and I - we were sort of part of the visitors. We were seen as somebody new. Whereas today, the people in charge are seen as somebody who walks around in a uniform. We were the workers of the park and we were sort of adopted, if you like, or perhaps the other way around... I'm not sure. But we made a lot of friends in those early days and a few of them are still alive. Graeme and Shirley Hart, who were there last weekend [at the 50th celebration]. The Harts were amongst our first visitors and they're still going. And their family. Their kids were only little tykes when we first got to know them. I think that's a good indication of how the early days at Girraween developed, because after all those years - you know, fifty years or so - we still have close friends - the Harts, the Cliffords from Kingaroy... They're still our close friends.

|

|

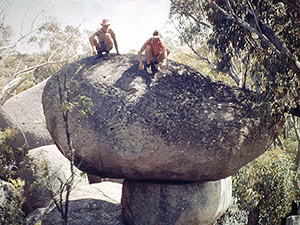

Tom and Graeme Hart rock climbing.

|

|

Well, I know that their granddaughter is very interested in Girraween, because she's contacted me a couple of times about it. So it's definitely in the family.

Well, they have a terrific knowledge of Girraween, because those kids, Dave and Shirley had four kids I think, they all became bush walkers. They learned how to swim. They learned how to climb difficult places like Mt Norman and the Pyramids. Girraween was part of their education and I don't say that lightly because we don't see that enough in kids today. Kids today are tied up with their electronic wizardry and whatever. They don't appreciate what's out in the country like those kids... Graeme Harts' kids, the Cliffords, the Lowes from Kingaroy... They grew up and they appreciated what the bush is all about at Girraween.

What do you think is your biggest achievement that you did while you were working there?

|

|

Oh, no question about it. Apart from the physical stuff - the toilets and picnic ground - the biggest achievement was introducing so many people to the wonders of a wonderful area of nature. Girraween National Park. In between building toilets and picnic grounds and whatever, Bill and I, and to a lesser extent Hock Goebel, we went with people out in the bush - guiding them to places like The Sphinx and Mt Norman and all that sort of stuff. So without a doubt, that was I think my biggest achievement. Introducing so many people to the wonders of nature and the wonders of Girraween National Park.

Yeah. It's interesting. I've interviewed a couple of other people and I was expecting them to say something physical like, you know, I built this track or I built this something or rather, but a lot of them have said yeah - just meeting people, working with people. That's their best memory.

I think the majority of the visitors to Girraween National Park were genuine nature lovers. Whereas people who'd go to, say, Lamington or whatever, Tambourine and those places, they're just tourists, in other words. Whereas Girraween visitors, they're the real, true nature lovers.

Girraween is such a diverse place. Everything from rock climbing, to walkers, to wildflowers, to the night life. It's such a diverse place and I think that's the beauty of that place.

It's a heck of a job, given the visitation to Girraween, to keep it looking spick and span and what people expect when they go to a national park.

Yes, kudos to [the rangers]. Every time we've been there, the loos are in great condition. Always been clean. The picnic areas... So yeah.

They do a good job, they really do. Mind you, there's seven of them there, so you'd expect so. (Laughs.)

(Laughs.) Well, the numbers are getting bigger. You've got to take that into account now. It's not only Girraween that they're looking after, it's also - what is it? - Sundown and a whole lot of other areas as well.

|

|

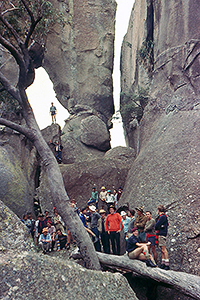

1967. Tom and Averil with visitors on top of the Pyramid. Averil is on the far left, with baby Shaun. Tom is seated on the far right.

Late 1960's or early '70's. Tour group at the Eye of the Needle on Mt Norman. That's Tom, standing in the Eye.

|

|

Yes, yes. And it's not just the physical side of the park. There's so many people go there and they have to look after the well-being of those visitors.

Yes.

That's a big worry. They have to ensure that the safety of those people is maintained all the time.

Definitely, yeah.

I think they've been lucky at Girraween, compared with places like Lamington and those places. There hasn't been a lot of serious accidents.

That's good to hear. Speaking of accidents and things, while you were there, did you experience any major fires, floods or other natural disasters?

|

|

Oh, we had a few floods. Not compared with what they've had there recently. I remember one in particular, Averil and I went down to the Junction. In those days, you could park on the side of the road and follow Ramsay Creek down to the Junction. And while we were down there, there was a heck of a storm come over and we had to hide underneath a rock for half an hour before we could get back to the car.

But fires... I didn't worry too much about fires because, when you read Alan Cunningham's report of Girraween, the whole vegetation of Girraween has changed since then. You know, the Aboriginal people used to use fire as a tool... And if a fire got into the park, I just used to let it burn itself out. Up to 200 years ago, it was a lot more open than it is today.

Right.

It'll be a major problem with the managers now because the vegetation is a lot more dense. So when a fire does get in there, irrespective of whether it's a fuel reduction burn or accidental burn, it's a mammoth task to try and control it. I don't envy those managers out there at Girraween, trying to control fires whether they're wildfires or fuel reduction burns. Big job.

Yeah. We'll move on from fire to snow. Did it ever snow during your time at Girraween?

(Laughs.) Did it ever snow! Yeah! The real big snowfall was in... I think it was 1968. The whole flat area, which was all the house yard and now the picnic ground, there was about two inches of snow all over that flat country. Up in the high ridges, it was up to four feet or 1200 mm deep. Some of those deposits up there lasted for four days before they melted. The road up from Bill Goebel's turnoff, off towards Dr Roberts Waterhole, that was actually closed to conventional vehicles for a few hours - the snow was that deep across the road.

Wow!

Winters then were, I think, different to what they are today. We had some exceptionally cold winters. Very very cold. An example... Averil used to take a glass of water and put it on the table beside our bed. That used to freeze beside our bed. Water in the kettle on the stove would freeze. We'd have a stick in the toilet to break the ice before we could use the toilet of the morning. That's how cold it used to get. And it wasn't just for a couple of days, we'd get a fortnight at a time of exceptionally cold nights. And that's what made the Granite Belt such a productive fruit thing because of the cold winters.

|

|

Betty Goebel and girls looking at floods. This was taken near where the Bill Goebel Bridge is now situated.

Snowing on the front garden of Gunn's Cottage.

Snow in the park.

|

|

I suppose it killed all the bugs on the trees.

It surely did. That was one benefit of it. We didn't mind because where the house where we lived was sheltered behind those big boulders on the western side. So we didn't get that cold westerly wind that you get at, say, Toowoomba or whatever. And we had a fireplace in the house, so the house itself was quite warm.

You know we spent - Bill and Hock and I, and Johnny Rogers later on - we probably spent three years in total building toilets and picnic tables and that sort of stuff. So we were out in the open a heck of a lot, but I don't know whether we were young and stupid, we didn't seem to worry too much about it. We got the job done, that was the main thing.

|

|

Right, yeah. (Laughs.) You mention the house... So where did you live when you were working in Girraween?

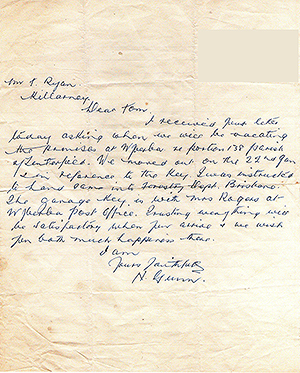

In the Gunn house. I think I might have sent you down a copy of it... Boy Gunn sent me a letter to say where I could pick up the key.

Yes, you did.

We moved there after we came back from our Honeymoon. Averil's older brother brought our furniture...what we had. We didn't have much furniture in those days. And Averil had a piano - a big heavy piano - which went into the lounge room. The floor of the lounge room sank, so Bill and I had to get underneath it and put some more blocks underneath it to stop the piano from falling through the floor.

That house, it was an old farm house from near Wallangarra. The early years of the Second World War, the Government resumed a lot of farms around Wallangarra to establish an ammunitions base and they auctioned off all the farm buildings. Boy Gun bought that building and demolished it and rebuilt it there on the site. So the centre part of that house is an old farm house from Wallangarra. Gunn's added the verandahs and whatever around the outside, but that's its history.

|

|

Napier Gunn's letter to Tom.

|

|

And Boy Gunn, by the way, was a relation of Aeneas Gunn from "We of the Never Never" fame.

Oh right! Small world.

They were a lovely couple, Mr and Mrs Gunn. They were rather sad to be leaving there, but they were quite elderly, so they took the opportunity to move on. But that's the story of the house. Unfortunately, it's been changed a little bit since we left, inside. But we had nearly six happy years there. Our two sons - it was their first home. They were both born in Stanthorpe and that was their first home. Part of our family history.

You mentioned your wife, Averil. What did she do while you were out at work in the park?

Well, apart from looking after two kids, Averil was the face of the national park. The unpaid, unheralded face of the national park. The office was on part of the verandah. I'd made an office there - put those steps on the picnic ground side of the house, that landing, I built that there and opened it up for an office. It didn't really matter whether we had a sign up "Office Closed" or whatever, a lot of people chose to ignore that, so she was kept really busy talking to people. It got to the stage where I signed forty or fifty camping permits - which were obligatory in those days - and Averil just used to fill out the details. She did that, you know, for several years and, I think I might have mentioned this last weekend, Averil and later on Leanne Grimshaw they never ever received any official recognition. Not that they asked for it, but that was just part of the job. It's a bit frustrating when, particularly Averil, she was the face of the park for a long, long time.

|

|

And then we started holding slide nights in the house, as I accumulated a collection of natural history slides. We'd have slides in the house and then when the shed was built, we used to hold them out there and Averil used to cook pikelets and scones and all that sort of stuff. We bought a two gallon billy which we used to make tea in. So after the slide show, it was a social event, if you like, just talking to people and Averil was sort of one of the main stays of the whole night. That's how Girraween was, I'm afraid, in those days. It was a family affair.

Well, that's great. I'm sure, as you're saying, there's lots of happy memories with that?

Oh yeah. Very much so, very much so.

|

|

The title slide used on the Slide Nights.

|

|

So you said you've got two sons that were born while you were there and started growing up. Where did they go to school?

Well, when Shaun was getting school age National Parks went through a traumatic era, if you like. The National Parks and Wildlife Service was formed. They created the four regions in Queensland - Brisbane, Maryborough, Rockhampton and Cairns. In each one of those, there was a Regional Superintendent. I was appointed the Maryborough Regional Superintendent, which was convenient because Shaun was of school age. So we went there and he started school in Maryborough, as did Chris a few years later.

So they were too young to go to school when you were in Girraween?

The next year, Shaun would have been okay because the school was still at Wyberba.

Right.

But the opportunity - it was a huge jump in position and salary and whatever - to go from a District Ranger to a Regional Superintendent.

Yep. Back on to Girraween and your family. Did you get out much as a family into the park?

Oh yes, yes. Averil went up the Pyramid when she was [pregnant]. I don't know which one she was expecting, whether it was Shaun or Chris... But after Chris was born, no, she didn't get out that much.

|

|

Bill Goebel's mother, old Granny Goebel, she and Hock's wife, Betty, they were sort of the only females in the district - in that part of Wyberba Valley. So they became fairly close friends. Old Granny Goebel, I think, she treated Averil as a sort of pseudo-daughter, if you like. She was a lovely old lady, Mrs Goebel. As was Betty, Hock's wife. So I think it's probably fair to say that we were our own little community. Averil and I and the two boys and Betty Goebel and Granny Goebel and, to a lesser degree I suppose, Mrs Rogers at the Post Office.

She was a great help to us, particularly with the phone because, in those days, the phone was only available for a certain number of hours. But Mrs Rogers always said to us "if you ever have to make a call after hours, I'm always here". Which was great, because we knew we had that facility if we needed it.

It would be a big comfort if you had an emergency.

Oh, my word. Not that we had many. We never had any crime to speak of. We never had any trouble with visitors. They were all bushwalkers. Nature lovers.

|

|

2006. Tom, Averil, grandson Matthew Ryan, and Betty Goebel at the park's 40th celebrations.

|

|

That's true, yeah. So... What is your fondest memory of Girraween?

My fondest memory of Girraween, is Girraween. I just couldn't pick any one thing, because there's so much diversity. The typography, the botanical stuff, the natural history, the birds and the bees and whatever... No, I couldn't give you one favourite bit - just the whole national park's area. A terrific place. Unique. Unique in Australia, that park.

Yep. Ah, just going through the list of questions here... You've already mentioned why you left. You were offered a significant promotion and pay rise. I think that's quite understandable.

Up until then, there was no such thing as a District Ranger. They created this new position [at Lamington] for District Ranger and that's what I filled. Even though we lived at Binna Burra, I spent very little time there because I was in charge of a whole heap of national parks.

|

|

Do you have any other interesting stories or anecdotes about Girraween that you'd like to share?

There was one thing that I've never been able to solve. Obviously, in the early days, a lot of prospectors and whatever wandered through there. Bill Goebel and I used to do a lot of exploring, you know, under boulders and whatever. In one place we found an old tobacco tin - Yacht Tobacco - full of molybdenite, which is a metal, and an old 22 rifle hidden underneath this rock. In another place somewhere we found an old Dutch Gin bottle with a whole heap of little canvas bags which obviously were going to be used for whatever he'd found... Which suggested that there was European people in that country a heck of a long time before orchards started. So that's just a part of the mystery of Girraween. We know that, well, there's a story anyway that Thunderbolt actually was within that area at one time.

The other interesting thing [is] that all around the Wyberba Valley and down to Wallangarra, there's lots of signs of prospectors, but I never found anything in what's now Girraween National Park [to show] that people were actually prospecting tin, or whatever.

Aboriginal occupation, yes. There's lots of indications of that. Particularly around the house. I found a wonderful double-edged axe and a spear head which is now in the display at the Information Centre. There was the mysterious so-called Aboriginal Well, which isn't an Aboriginal Well, but it looks like it could be. Whatever caused it, nobody knows. Where the water comes from...it's always got water in it, in the middle of nowhere.

So apart from the botanical, the rarity in the botanical side of it, there's all those mysterious little things. You know? Who made it and why was it made? Where are those people? What did they do? What were they doing there? All those little sort of things.

|

|

The hidden bags and bottles.

The stone axe head.

|

|

And I think the other magic thing about Girraween is the bird life and the native orchids. Unique in Australia, I think. The number of birds that were there and the little ground, terrestrial, orchids. Quite unique.

I was lucky when I first went there that I had people like David Hockings and Jean Harslett and Percy Grant and those people who had a fair knowledge of botany and bird life. They spent a lot of time with me at Girraween teaching...well not teaching me...but showing or giving me the names of all those things. Jean Harslett in particular. She wrote pages and pages and pages of botanical stuff on native orchids, which I still have, by the way.

They're the sort of thing, I think, that sort of humanized my time at Girraween. They weren't professionals, they were just homespun experts. Particularly Jean Harslett and Percy Grant. Unfortunately, they are now both deceased. David Hockings... I'm not sure.

So they are slowly disappearing and, as I said to somebody the other day, of all those people from my era, I'm probably one of the last. Sid Curtis is dead, Billy Wilkes is dead, they're all gone. You know, I'm 75, so I'm sort of approaching the end of that part of the history of Girraween too, sadly. I think it's extremely important that somebody, like yourself, is recording the history of that park. It's been a favourite concern of mine, if you like, for years.

Using Lamington as an example, hundreds and hundreds of workers have gone through that place since the start of it in the 1930's. Nobody knows who they were. Their names are gone. I think that's rather unfortunate, so I think it should be recorded somewhere. I think the chap that was there [at Girraween's 50th celebrations] from National Parks last weekend, I think it was a bit of an eye-opener to him to see that a lot of people are really interested in the human part of Girraween National Park. I don't know if you heard him, but he did say that he's going to take those concerns back to Brisbane. So hopefully, hopefully there is an interest outside of the park of its history. Most important.

That's excellent that the gentleman is going to take the message back to Head Office. Yeah, well we're doing our little bit by speaking to people, such as yourself. I have to say that it is a real pleasure doing it because it's nice to hear about the people. I mean, you go there and you can see the rocks and the plants and that, but just hearing about the people who have worked there and lived there really, well to me, it brings the place alive. Gives it that extra facet.

It certainly does. A favourite word of mine is that it "humanizes" it. A place like Girraween isn't just the rocks and the flowers and the creek and whatever, there's the people that were there. I think that the work that a lot of people have done has made it more attractive and useable by so many people. Most important.

Yep. Well, speaking about the work that's been done, that brings me to my last question. How much has changed in Girraween since you were there last?

Oh, I think it's probably fair to say that the developed - there's that word again - part of Girraween that I left no longer exists. The house gardens are all gone. All of those trees have grown up... The Information Centre there... All the buildings that have got built or are gone... So it's a different scenario to the one I left. Yeah, I don't know how to put it. The Girraween that we left has changed tremendously. I'm not sure if it's for better or for worse, it's just different.

Did you plant all those trees that are in the picnic area?

Ninety nine percent of them, yes.

And they're from local seeds and things?

I built a little nursery behind the shed and Bill and I collected seeds all over the park. The Stringybarks and the stuff from Mt Norman. We propagated all of those trees and when they were about a foot high, we planted them all through that picnic ground. I think it was 90 that we planted - it was under 100, anyway. A lot of them died. The rabbits...

That was one of the problems that I did have there, was rabbits, but I kept them under control through trapping and I had approval from Head Office to shoot the things when it was safe. But a lot of the trees that are there now, the stuff that Bill and I - and Hock, I think - planted. Paul Grimshaw did plant some, but certainly the majority are what Bill and I planted.

|

|

It certainly does make that a very nice picnic area.

It's lovely. Although, what sort of detracts a little bit is that concrete path that runs out through the middle. I would have probably done it differently, but everybody to their likes and loves, I suppose.

I think they are trying to make it more wheelchair friendly.

Oh, they have to do that, yeah. I'm not disputing the necessity.

I know Jo's put her heart and soul into the interpretation of some of the things, which is good. You know, what remains of the old buildings and that we built, she's got a lot of interpretive stuff there. I noticed a lot of people were reading that sort of thing.

|

|

An interpretive display in Gunn's Cottage.

|

|

People today, Girraween particularly, want to know about the park. Whereas, we were in Lamington just before Christmas for Lamington's 100th birthday and I took particular notice that people just turned up, got out of their car and just took off up the walking track. And they only did it because there was a walking track there. I don't think they were particularly interested in what they were going to see. It was so they could go home and look at the photos they took and say "this was the weekend we went to Binna Burra". People who go to Girraween, they're really interested in what's there because it's, as I said before, it's unique. So different. And it's going to stay that way, luckily.

I really think it's important that humans are seen to be a part of the national park. As long as they [still] promote the park for what it is, of course. I think that's one beauty about Girraween. That Information Centre - there's always somebody there to be seen. That's most important. Most important. And I think the new ranger there, his heart is set on keeping Girraween as it is. He's gonna do a good job, I think, that young fellow. Best of British luck to him.

I haven't spoken much with Greg but he seems to be a very nice, down to earth gentleman. And he's keen on wildflowers, so that's a big plus in my books.

That's how we took him. We had a - oh, not a long - conversation with him and his wife just before we left and I got the impression that he's going to be a real asset to that park. I hope he stays there a while. I think it's important that people are there for at least, at least four or five years so they can learn what the place is all about. It's such a complex place. It's not just the Pyramids and Mt Norman. There's a heck of a lot to learn.

And every park is different, too.

Oh, totally!

Anyway, I've got a feeling that the battery is going to run out on the phone...

Good to talk to you... and I hope what we've gone through helps a bit.

|

2006. Tom and Averil on the veranda of their first home, Gunn's Cottage.

|

|

2006. Averil with sons Shaun and Chris at a toilet block that Tom, Hock, Bill and Johnny Rogers built, now demolished.

|

Aerial view of Gunn's Cottage, 1967.

|

|