|

|

Executive Officer - Park Planner

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Services

Interviewer: Vanessa Ryan

NOTE: Trevor spoke for a while about the general history of Queensland National Parks before discussing Girraween.

The real visitor managers, the thinking, was in the US Forest Service. They had an extensive social research program. The Forest Service managed more wilderness land than the National Parks did - massive amounts of land that weren't just there as timber production.

|

|

|

I suspect, coming back to the lack of emphasis on empathy for the visitor, we got better at designing this sort of thing with landscape architects on staff and thinking about the details of design, but [also] in terms of the broader management of each park.

Maybe we should start talking about Girraween?

Yep. I was going to slip to Girraween. For Girraween, it's managed. Compare Girraween and Sundown. Girraween - a fairly sensitive environment, but lots of interesting things, easy access, and high scientific interest.

Oh definitely.

Sundown - it's hard as the Hogs of Hell. It's traprock country. The tracks that go down to Burrows Waterhole are probably the same as they were twenty years ago. It's shallow subsoil onto rock. The impacted topsoil is gone - they can't be impacted any more. And it's got a lot of fairly ordinary veg - there are some special species there, but generally they're not.

So given those two parks... To look after Girraween - you're going to have a lot of people. So concentrate their use into small areas and manage that use against impact. The walking tracks, the stuff they've done down there around the swimming pool and like what's happened here [the Visitor Information Centre]. Very high, intense hardening and managing the impact and changes that's coming from people. So you can have a boardwalk across a wetland that's full of rare species. There's the initial impact of putting the boardwalk in, but then afterwards...

So as far as that goes, Girraween - high use, high management, high interpretation effort; whereas Sundown, not so much. You don't need the interpretation people there. It's the pioneering type of people going there because it's a rougher place and they can get off and walk. They don't necessarily need to be guided down a walking track and then hop in the car and go home.

It's a different mindset.

Different mindset, different use, different customer set. But look at Girraween and Sundown in the region together - they're complimentary. Highly complimentary. So that's sort of why I was thinking about the management of Girraween versus Sundown. Seeing those two as being complimentary. Quite different - different user groups, different values.

So that was taken into account when it was decided to make the Information Centre here?

Probably. The thought hadn't really developed by then, but it was almost sort of self evident.

A lot more people were coming here than Sundown...

Yeah. And there was no way we were going to say, oh it's getting over used, we're gonna cut people out. We're going to close a camping area - when they'd bought the link for a camping area. So you're always the victim of your past decisions. (Laughs.)

Yes... Well, I've got a couple of questions here...

Go for it.

The first one is about the interview you did ten years ago with John Cowburn. You were described as a Park Planner for the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Services. So, what does a Park Planner do?

(Laughs.) Basically, what I was just saying. You're looking at areas in total, say - drawing up the Management Plan. Trying to look to the future and how to achieve what you want to achieve in the park.

So you look at a park, see how many people are using it, where they are wanting to go, what kind of people are coming?

Yep.

The geography of the park - where the tracks would be best to go, where the picnic areas and camping grounds should be... That sort of thing?

Yeah.

And how to develop it? You were saying about the 10 percent [usage] increase each year. Was that something you worked on - that this year there were this many people, so we need this many toilets, but in ten years time, we'll need another block of toilets?

It would be good to think we did that. (Laughs.) But say, look at Carnarvon. I'll use that as an example. We certainly made a lot of bad management decisions at Carnarvon, all for the best reasons.

The first thing was, the pioneers were going there - we'll put in a simple camping area with a pit toilet. That attracted more - so we'll have to put another pit toilet in. Oh, there's more people coming. Oh geeze, we'll put in a septic and we'll put in better fire places. More people coming - they're attracted by the newer things. And so we got to a point where we had 2,000 people at Carnarvon one Easter long weekend. That was in 1973 or '74. Easter coincided with Anzac weekend. It ended up a six day weekend.

So we had to respond to that. We had to fix the road - everyone was complaining about the road access... So what was happening? We changed what was called recreational setting, which is sort of dictated by the type of access, the type of facilities, the type of information given, which determines the type of visitor.

As you improve it, you go from the rough and ready, through to families with little kids and grandma and grandpa.

Yeah, what David Pips described as succession. First of all you have the pioneer explorers and it slowly gets to, in the end, the sedentary grey nomads.

And you end up with people in wheelchairs who can come along - like the Wyberba track.

So the thing for planning, is define where you want to fit in that spectrum from totally primitive to full on control and management. Still aesthetically right. Well designed, but catering for different people. So really, that's the challenge for park management. We didn't do that very well at all [at Carnarvon]. We did it here and at Sundown, not necessarily deliberately... (Laughs.)

A happy accident?

A happy accident.

So it would have been a learning process? As you were saying, the first parks were in the early 1900's and no one had ever done this sort of thing before.

You're spot on.

So over the years, you've learned as things happened. Oh, we did this and now people are doing that, so if we don't do this in a certain place, then we won't get more people if we keep the facilities fairly basic?

Well, what's management? What is management? Think about it. It's directing resources to achieve a desired outcome. If you don't know what your desired outcome is, you're just directing resources and things happen in spite of you.

So, we did a lot of directing resources... And really, what the planning is about, is defining your outcomes in terms of the recreational settings you are trying to create for people, recreational opportunities for people and also translate that through to your environmental management.

The classic thing - Epping Forest National Park. As a reserve, what's your prime objective for Epping Forest? We want to maintain and enhance the Hairy Nosed Wombat populations. That's the overriding objective. Ok, what have we gotta do about that? We may have to put fences around to keep out feral animals. We may have to put in artificial burrows for wombats to enhance breeding. We might have to intervene with the population - artificial insemination... God knows, whatever you like to achieve it. So that's where your management goes. It's not just saying it's a National Park - we do no development. I don't know if I'm making myself clear?

I understand what you mean.

Basically, every park will present a different set of goals and objectives. They might be subtly different. You know, if you look at the forests on Fraser Island. If you burn frequently, you'll get one suite of things. If you burn very infrequently, you get something else - get in scrub. So you gotta start thinking, hey, what are we doing here? What mix of the vegetation types do we want to maintain? That will determine what your fire management is going to be.

And look here, Girraween with fire. We had some workshops down here with the locals and we had National Parks Association people, we had 4 wheel drivers and that... And one of the objectives with fire management which really came out was "we don't want to burn out the bloody neighbours!" They'd give us heaps if we burned them out. A big embarrassing "no no". (Laughs.) So we set an objective that we don't want to lose any fires from the park. That immediately sets something down. Within that, how do we manage the different population of things, while not burning out of the park?

So part of your job would be to work out the burning schedules? You'd work with the locals on that?

Yeah. So we'd set that up. And that's influenced [the burning] here... Compared to across the border in New South Wales - the guys here burn far more frequently than at Bald Rock and Boonoo Boonoo.

So why is that? Why do they burn more frequently?

Because of that imperative. Well, that's one thing and that was sort of established. Probably, if you asked the guys here, they wouldn't [burn as often]. There's probably not a lot of scientific evidence to support the more frequent burning, but the gut thing was saying that this sort of stuff was always fire prone anyway.

I think the early records from when Cunningham came through, he said that the area had been burnt. Whether it was Aboriginals or [lightning]?

It's a very fire prone environment and if you don't do incremental little bits you end up like what happened over the border there in 2002 with the Ballandean fire, you might remember? People's lives were lost. It burned around here and then for a week or so later, then the weather conditions went bad, it crossed over into Bald Rock and burnt out all of Boonoo Boonoo, right down to Sandy Hill.

They burn infrequently. They have some sort of blanket description. They won't burn Eucalypt forests. They should go twelve years without being burnt, which is fair enough in an area - you should have some areas that go that long. (Taps across desk in a random pattern.) But you should be mosaicing it around. Like these guys here do smaller burns, more frequently, whereas over there they say: "oh, we've got to burn out this compartment". So they've got to have so many resources on site for the day and if it's not a good day to burn, there's a tendency of "we can't send them all home without doing anything, we'll burn". So it goes over hot and all that does is open it up for wattle. Then they don't come back for twelve years and in twelve years' time it's wall to wall wattle.

Something I read about Girraween is that since they've been doing the regular burning, they've lost certain species in some areas.

That could be right. Now, if that's the case, you've got to start looking at modifying the burning pattern. You will never know everything about every species in the park. And probably, they've all got competing requirements anyway. The sort of thing is, that you (taps desk again) that mosaic - it's a fairly old concept, it seems to me. But that's what planning is about.

So you do the fires, you do where the information centres go and picnics areas. What about things like the water and power?

That's probably not so much in the park plan. Well, if you say, here, we've got a camping area and we're going to have 300, 500 people here at Easter. You've got to sit down and say what's the water requirements for those?

So, it is sort of taken into account?

Yeah. Say, how many toilets do you need to be able to manage that? What sort of support services do you need to clear rubbish away? Or what sort of interpretive programs do you need - what's the nature of the interpretive programs for this particular situation? Is it promoting the diversity of the park, or trying to modify visitor behaviour?

So you are doing everything from the basic needs of the park - as in protecting areas - where people can go. You're looking at the park and the environment it's set up for, as well as the visitors and trying to strike a happy balance.

|

|

And looking ahead. Parks aren't uniform. So that here we've got this visitor node where we'll have walking tracks that are paved, safe 100 percent, hand rails... Lots of interpretive signage and all that.

Whereas, we've got a walking track to the first Pyramid. We won't change the track up to the Pyramid - you can't do much about it. And then you have, oh, Mt Norman. There's a walking track out there. Those tracks will be not quite as smart as these, but they'll still be graded, narrower ...

A few steps put in?

|

|

|

|

Yup. Whereas then, the second Pyramid and other things, we won't have anything. But if you write in the management plan that if walking tracks out there develop beyond a certain impact - you know, they might just be a bush pad to follow and that's ok - but if it gets to the point where the bush pad's now becoming eroded, we'll have to do something about it.

I think that's happening out near Underground Creek. They've maintained the main track that goes to where the rocks are, but there's a little track that I don't think was official that went up around the side so you can get up on the rocks, behind it. When we originally came and looked at it, it was just a little path where people went. I think it's now been widened.

In my management planning thinking, the Underground River and that would be part of a main visitor impact recreation place.

Yeah. You see, everyone who gets there, the urge is to go up behind and, oh, there's this side trail. I can see that in the future they will have to develop that side trail just to prevent people from damaging things.

Yeah.

You mentioned the toilet blocks with the planning side of things. When we were talking on the phone, you said that they all have rock walls. Was there a standard design for toilets?

That was pretty much the standard. It really kicked in around about '62, because of Bill Wilkes... I have a lot of respect for Bill. He was the best manager. He could move material on his desk as Secretary. He would give you a job, he would chase you up and if he ticked you off, but you didn't feel as if you've been ticked off. All you would feel was, I'm going to do better.

He sounds like a good bloke.

He was a good manager.

So was it one of his pet projects that every toilet should be like this?

|

|

Well, he went to America and attended the first world conference on national parks in '62. He came back and one of his recommendations was that National Parks should have a biologist in its management and that's when Syd Curtis was appointed. Syd was a forester, but he was very much a biologist in general and had natural history interests. He was the nucleus of the National Parks branch.

Bill brought back this folder of photos of US park service facilities. Bill was interested in facilities. And a lot of that had random stone walls, signs that had stone columns and it was very, what I'd describe as, US National Parks woodsy. Folk woodsy. (Laughs) So that was the reference book, oh yeah, for picnic tables and the toilets. That sort of thing. It grew out of that. It was the standard right across the state. He standardised the colour scheme, which was chocolate and yellow. A heavy, dark chocolate and yellow.

|

|

An example of US National Parks signage.

|

|

It worked well in the rainforest areas, which was basically the emphasis of a lot of the Queensland parks that visitors used anyway. Springbrook, Tambourine, you know, that sort of place. Red soil, deep greens - it sort of worked. And in North Queensland. Not so good here. So he standardised that. He insisted that they had to be. And he said, we want it so that anyone who sees those colours knows they are going to a national park and they can expect they are going to have clean toilets.

I went on a few trips with him out of Brisbane...he didn't get out much. He'd go to a park and the first thing he'd do was walk into the Women's toilets to have a look. Now, he wasn't queer...

I was going to say! He made sure no one was in there first? (Both laugh.)

The women's toilets were always the management nightmare. They are harder to keep clean and maintain than the men's for some reason. So if anything was out of place, he'd come out and - as I said before, he had this ability to tick you off and draw your attention to it without putting you down...

That just needs a clean... Some kid's thrown up in there.

Yeah. Or that graffiti, you know? Any graffiti is cleaned up. First time you see it, you clean it. You don't say, I'll come back and do that next week. He insisted on things looking [good]. Oh, there was one [time] they built a shelter shed and he went and saw it and said: "That looks ugly there. Move it." They pulled it down and moved it. Which, well, why not? Why keep looking at something ugly and out of place?

Yeah. If it's going to be there for a hundred years, you've got to have it in the right place.

Ok, my next question. When was the first time you were involved with Girraween?

My first trip to Girraween was in 1964. Bushwalking trip.

So it was a personal trip?

Yeah. I was still at university then. I was with some people from the university bushwalking club.

What were you studying at uni?

Forestry.

So you had planned to get into the Forestry Department?

Oh yeah. I had a scholarship.

This was because you were interested in the bush and that sort of thing?

Oh yeah.

Do you have a particular interest in either botany or animals?

Nope. Just landscape. Harmony. That sort of stuff.

Do you know geology as well?

I know a little bit, but not lots. I find all of it interesting.

So, just a general or holistic interest?

Yeah. And that sort of gets back to the overall planning sort of thing. Bringing in all those other things - all the specialities together and considerations.

Seeing the big picture.

And I always came at it as a park visitor. Because I originally got interested in forestry and that sort of thing and the outdoors from going bush walking as a high school kid. I lived at Southport and one of my outstanding memories which turned me on to the bush was - I would have been seven years old - going up to Springbrook and down to the bottom of Perlingbrook Falls. Wow. What a place, eh?

Do you have a thing about waterfalls?

No, no, it was just the place. Rock walls, drama. The walk down, the cliffs, the rainforest. And that was only allowed by that walking track. You know? So that's sort of where I liked going. Not that we went up there much.

That's one of your favourite places?

Yeah, yeah.

So that was your personal first contact. When was your first professional contact with Girraween?

I started in the National Parks section of Forestry beginning of 1970. So 1970 would have been the first time I came down here as work. Tom was here and it was pretty much at the stage where they just camped out down here. (Indicated the now Day-use Area.) And there was a water tank somewhere just in here.

Yeah, I've seen photos.

|

|

It was up on poles... Two thousand gallon thing... So that's about where things were at then.

So pretty basic.

Yes, still very basic.

So when you came here, was it just a visit just to see the park, or was it actually to start planning?

There was very little planning in anyone's minds. We were reacting to pressures like at Carnarvon. More people, more toilets. More people, bigger toilets... More people, more cars - bitumen the road. And all the time you're becoming more and more sophisticated.

|

|

|

|

So when you look around now, things have definitely changed a lot.

Oh, it's great.

Is a lot of what's in place what you had in mind?

Well, I don't know what we really had in mind back then. This was all just bare - you've probably seen the early photos. They hadn't long pulled up the [apple trees.] Tom had just planted the gums and that all the way down there. They took ages to develop. They're forty years old, those trees.

So Tom Ryan planted the trees in the picnic area?

He would have, yeah, and Bill. So, when they bought it, they ripped out the apples. And the same over the other side.

My father took a photo from the top of the Pyramids [in the 1950s] and it was just all apple orchards and stone fruit. So they had a lot of work.

Oh yeah. It was the same up at the other camping area, going back that way to the other house.

Around Gunn's, ah not Gunn's - Thomas's?

I don't know what they called it... Yeah. But that was all apple orchards in there, too.

That's where the barracks are now and the workshops. And the ground... There's still an open paddock and it's still like this. (Motions up and down with hands.) They didn't do much levelling after they ripped the trees out. But they are re-establishing a lot of the plants. You wouldn't know where a lot of the old farms were these days.

Yeah. Even coming in. There were orchards all along the road.

They've done a lot of revegetation. It's amazing. I've got a few photos on the website taken at different times from the Pyramid, all looking at the same area. And you can see how the trees are building up over time. It's really cool to see that.

But there's still a lot of country out there to grow back over. I think that was McMeniman's land - cleared country.

But it's coming and it's a long term project. It's definitely there and it's happening.

While we are talking about the old farms, did you have much to do with the land acquisitions?

Most of the land acquisitions were post '75, by National Parks and Wildlife Services as I might have explained earlier.

Yes, you did. You were talking about what other people did and I was just wondering what you personally had to do.

Not a lot. The only credit I can claim is that when I was coming down here, when Tom was here and Paul, there were already some proposals to acquire land. But they were scattered all over the place. There was never an enunciated "hey, we want to acquire the whole valley". And basically, Syd Curtis had worked on some of those proposals. The way the Forestry filing system worked, each block of land that was being looked at had its own file. But nowhere was it sort of enunciated "this is a part of that and a part of that" to make the whole.

So it was just like looking at little bits rather than the big picture at the time.

Yeah. Putting it into the bigger picture. And then about '74, Mike Harris, who was a newly graduated Forester, got assigned to National Parks section.

Yes. You were saying he did a fantastic job? He came through.

Yeah. He turned up and Syd said to me, "oh, we'll have to think of something for him to do. You give him a job." It came out of the blue in about a week. I'd been on a trip down here and I'd been talking to Tom. Sitting up on top of the Pyramid. And Tom had raised the issue of the land acquisitions and whether Tom suggested we get the whole valley, or I, or if it was just the way the conversation went. That's when it set in my mind. It might have even been Paul... My memory's slipping.

But anyway, so I said to Mike Harris: "go there and look at everything in the whole valley. Stuff that hadn't been even looked at. Each block - plan what's on it and how it fits together...and I want it all bound up into one spiral book." So all those proposals were related with photos and stuff. That had just been done and then the Parks and Wildlife Services was set up. We had John Churchwood and the acquisitions and another chap, Ken Green?, and John was sent to pick up this report and he ran with it. He just kept flogging and it was just sort of lucky that it was there.

So, some of the farmers were happy to sell up and some of them weren't, from what I hear.

John wore them down.

So they were all happy to stay, but he heckled them?

[Laughs...] He just kept coming down and he'd talk and talk...

I've been in contact with someone who was one of the people who lived here and apparently the first offer was - and this is what he says - for half the value of his property and he wasn't happy with that. Eventually, I think he sold at three quarters the value.

Well, I'll put this into context - how the Government acquired land. They had the Lands Department do the valuation for us. The same as if you went to a Real Estate and said "hey, what's this land worth?". Look at what's there... They would set a price from their valuation and that was the offer. This is the process we are talking about now. If the landholder, subject to resumption, felt he was being downed or dudded, he could appeal to the Land Court. The Land Court could then review the valuation, hear what he said, and would make a decision. There were only two very unwilling sellers here. Most of the landholders sold and they were probably glad to get out. That's my feeling.

|

|

[They were] scraping by?

Yes, it's poor country, but the land's pretty. But they were all negotiated settlements, except for Ward and Saunders - that's the round stone fort - and Ky Knealing - the arches and the old stone house over at the other side of Mt Norman.

They were the ones who wanted to have the horse ranch or something?

Yep. And Ward and Saunders were looking for a place to drop out. They hung on to the end. Now, I can't recollect if the resumption notices were issued. But none of it went to the Land Court. So they were all negotiated deals. Those people agreed to sell. They weren't having their arms chopped off.

I knew that wouldn't have happened. It's just interesting how you hear the two sides of the story. So yeah.

The Government is - the process...

It's bound by Law.

Yeah, it is. The Lands Act governs all that. The resumption notices are issued and if they don't like the valuation, they can appeal.

I've recently just been looking at some of the old brochures. Tom Ryan's one, that he did by hand by himself, and one that Paul Grimshaw had, which I think was an officially printed one. And it's interesting. Both of them have got maps of the park on them and you can see how the park's developed. Tom's is just a few areas and Paul's is a bit bigger...

|

|

The now ruined Round House.

The entrance to the old Knealing property.

|

|

Well, if you have a look at that aerial photo in there... Did you see that when we came in?

Yeah. I want to have another look at it later.

That sort of sets out what the park was in '70...'71?

It's interesting to see how the borders were different back then and how much land has been made a part of the park.

Oh, it was amazing.

Were there offers made on the land that's now that Girraween Environmental Center? You know, on the way in?

The Lodge? No. That was actually owned by Binna Burra at the time and the main focus was the valley. And it being owned by Binna Burra, the thinking was that they were going to develop a Binna Burra type resort, which would fit in the management concept we were talking about. The visitor concentration down on this end and then that could have been linked with a good walking track from up there and back, so people from there could access down here. So that really was why it wasn't really considered.

Ok. When you look at a map, the park's sort of around it now. There's this big empty box...that sort of thing. Maybe in the future it will become a part of the park?

Maybe, but you know, is it that important?

That's true. I guess I'm just one of those people who when they see a hole in the middle of something, I want to fill it... (Laughs.)

You've already mentioned about the Information Centre - how it was so obvious where it was to go and how it was to point in the direction looking at the Pyramid. Who were you with?

|

|

The Works Department architect was Frank Turvey. We hit it off fairly well, too. I had sort of studied landscape architecture at that time, but I never finished the course, but I at least had an interest in design. And I could understand the architect's language. So we just sat there and sketched it out. I picked the site. I said, "look, it's got to be here near these rocky boulders...and this becomes the entrance, down through those rocks. You build that up and that sort of sinks the building in." The visibility from here gives you that "wow" - you got to have that view of the Pyramids.

The big windows... yeah. That's great. You go in and you just look out and you can see the Pyramids.

Yeah, it was pretty self evident. And it had to be rock here...a rocky place. We also had the theme of the rock walls...

|

|

June 1977, Info Centre Construction.

|

|

It works and the guys seem to enjoy working there.

Oh, I think it's a lovely building.

I really like how it's got the two sections. There's the working section for the rangers - their offices and that - but when you walk in, there's that lovely display.

Well, a criticism from the interpretive people was "oh, there's not enough room for a display. And you don't have visitor's centres that have windows..."

I think it works well.

I think it's ok. I said, look, the function is really to give the guys a place to meet the public. You can't have them coming knocking on Tom Ryan's door...

As they used to!

...to get a camping permit. You know? Give him an office and a place and a bit of a display. I saw it a little bit differently. It would have been great to have built up a botanical collection for the park.

I think they did have a folder, but it's ended up at the Herbarium.

So I sort of saw it as a resource [centre]. The books, the library. Just basic stuff like that. At that stage, Overseers didn't have that sort of stuff out in the park.

Really?

Yeah. So the idea was - to my mind - people come there, make contact, get orientation. This is where you are, this is where the walks are. Go out... Need information... You're curious... Come back.

Yeah. I saw this bird... It looked like this... What was it?

And we've got the answer for you. That's what I saw.

The interpreters had this sort of thing about their signs, you know? "Stop, listen to the sounds of nature." I sort of argue that you go down along the waterway there - you know, where that little platform is? You don't need a sign there telling you about waterholes. Hey, you're just there soaking it up.

I think they might be thinking about schoolkids, when they come out on their day trip and they've got to learn.

Well, design it for them. When I went down the bottom of Purlingbrook Falls as a kid, I didn't need to have all that rubbish. Oh, it's not rubbish...but...

I know what you mean.

Nature speaks for itself. You know? Beauty and stuff. Like just down there by the waterhole - you get the peace and quiet.

So, do you find that sort of signage obtrusive?

I find it, yeah. It's got to be very subtle. Some signage can be brilliant, but it's got to be... you know. Because, otherwise, I come here to see a national park, not all this fruit salad of signs...

A couple more questions... The park Overseers, as they were called back then, like Tom and Paul... Did you have much to do with them?

When I started in National Parks, Bill Wilkes was the Secretary managing them and, so in southern Queensland right out to Carnarvon, they had a Park Ranger which was a salaried position. His name was Herbie Hausknect. Tom would really explain...

Yeah, he's in Tom's book.

Ah yeah. He'd come down here for work and he'd have carpet slippers on... Oh, you know?

(Laughs.) Some real characters...

He was. But before then, there was Jack Greste and, earlier than that, George Gentry. They would supervise all the track construction and stuff. They were park lovers. They were nature lovers.

And so, they had the position of Ranger?

Yeah.

And under them were the Overseers?

Yup. And then there was a Ranger position at Mackay, looking after the Whitsundays...

Sort of regional position?

Yeah. And there was a Ranger at Atherton Tableland, looking after all that north Queensland stuff. Townsville and that. So then, my position, I came in and I sort of took over the co-ordinating role for park works - with the three Rangers. I'd do the annual budget estimates, the work programs. If you wanted a new toilet block somewhere, I'd get the plans done and budgeted. The Rangers basically supervised them. So that was my sort of role - budgeting the parks works stuff. And all the southern national parks then, there was Peter Ogilvie who was a zoologist.

I know that name from somewhere...

Yeah, if you really want history, Peter would be a good one to talk about history. And Peter Stanton... You may have heard of Peter? He was basically doing park proposals. There was a lot of stuff he started doing... Systematically looking at the state - about where park acquisition should be. Cape York and all of those things. And I sort of came in looking after the facilities of them and the management. And Syd Curtis was OC.

So when you were working, you were based in Brisbane?

In Brisbane. Yeah.

When we were on the phone, you were saying that you had great respect for Tom and Paul because they had such enthusiasm and that, in those days, park rangers were chosen more for enthusiasm than qualifications - like University qualifications. Did I understand you correctly there?

|

|

They were chosen for enthusiasm, but then, as I said, their position was designated Overseer. They were on wages. The next step up from that was Ranger, they were salaried. I was salaried as a Forester. So Tom and Paul, they started off as Workmen and got promoted up. And, oh, Long, he's not there now... And Peter Haselgrove at Sundown...

I've met Peter.

Peter is actually a geologist.

Is he?

Yeah. Well, the story I was about to say... Tom started at Ravensbourne as a Workman and Bill Wilkes home was up there. So Bill always had a soft spot for Ravensbourne. And then Tom was appointed Overseer here.

|

|

Peter Haselgrove (left)) and Paul Grimshaw.

|

|

I think he had one week's notice.

Could have been. (Laughs.)

He was sort of told, out of the blue, you're going to Girraween.

Paul, he worked in Brisbane. We were in the old Wills building, across the street from St. John's Cathedral, next to the old Fire Brigade.

That the Forestry Building, was it? It had a big slice of an old tree in the front entrance?

Yep. And an old lift that had a cage. We were on the top floor. The clerk, one day, said: this guy keeps coming in, looking for a job. Have a talk to him. It was Paul. I talked to him and look, there's no vacancies around... I think he was installing shower screens [at the time], or something. He kept coming in and I said, look, there's only one job I know that's available - it's a Workman at Carnarvon. I said, the problem is we've got - and he was married - there's no married accommodation and single accommodation was thin prefab rooms with a central thing with a corrugated iron galley that had a wood stove in it. Very primitive. And he said, that's all right. I'll buy a caravan. (Laughs.)

He was eager!

Eager is eager, eh? So he went out there and he started to collect stuff and information about the park. And then when Tom left here, Paul was a natural to step in as an Overseer job with his enthusiasm.

Yeah. Were they unusual in the fact that they were so enthusiastic - compared to other Overseers? Or were they all like that back then?

Well, Bill Goebel. He was enthusiastic...

I was just thinking of other national parks around Queensland. Were their Overseers sort of similar?

They were probably the standouts in that enthusiasm. Peter Haselgrove, he was the same. He kept coming in at work, there in the Wills Building, the same as Paul. And, I think we had a position vacant up at Mt Glorious. So he went up to Mt Glorious. You know, some people just stand out and they get the job.

|

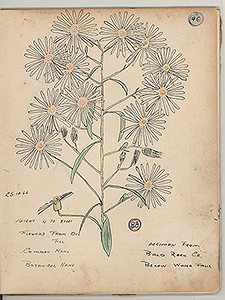

I know that Tom, one of his passions was recording the wildflowers in the area. He's lent me his little book that he did all his drawings in. You know, it was basically one of the first records of plants for the park. I believe Paul carried on from that. And Paul's given me lists of mammals and things that he'd seen. Were all the Overseers doing this sort of work?

No, no. Some of them were very basic people. Very very basic people. I'm not necessarily saying they didn't - like the old chap, Bill Moyne. He was at Springbrook - a real gentleman. Particular about doing park work and stuff. He loved the Parks. Excellent photographer - birds, wildflowers, but not necessarily collecting names and categorizing them. He was the Overseer at Carnarvon. So he had that interest. And the fellow who was at Carnarvon before Bill, Charlie Brockhurst. He was barely literate, but he could tell you anything about that park.

|

|

One of Tom Ryan's botanical drawings.

|

|

I'm thinking about how there are the different kinds of people. There are the ones who have the knowledge, an astounding knowledge about nature and whatever, but it's not in them to write lists of what they see and record what their knowledge is. They just want to experience it. It's a shame that they don't want to do that, because so much of that experience is going to be lost. So that's why I see people like Tom and Paul are of special interest, because they have actually sat down and recorded things for posterity and that people can build on. It's a shame that other people haven't been doing that as much.

Yeah, but other predecessors, one of the first Overseers at Lamington - Gus Kuskos - a rough sort of a fellow - but his knowledge of the park and the species and that - like some rare orchid - you see a flower poking out of the ground and that's it and then it's gone. He was highly respected by the park visitors going there and the scientists.

Hopefully people from outside the parks, like the Herbarium and the Museum and that, have had a lot of contact with these people and gleaned their knowledge so it's not lost? And Bill, Bill Goebel. You started to speak about him. He's an amazing gentleman. Did you have much to do with him?

Not with Bill, no. He was a Workman here. Not a lot of close contact with him at all. His brother, Hock, also worked here. And there was another fellow - oh... Bert Walker? - he moved from park to park. He was a carpenter and I suspect Bert would have worked on the first toilets and the shed over here, with Tom. Tom might have a better idea of that. But Bert, again, a very simple gentleman. Long term member of the National Parks Association. He just loved nature.

Getting out and seeing it and experiencing it...

Yep. And it expressed in his work. Bert could make a walking track, you know, with a mattock - a couple of swipes and he'd drop a rock in and there it would be. Can you do that? (Laughs.) Right, that's one... And the next one... Swipe, dunk...

I suppose when you have a couple of kilometres of track to do and it's hot weather, you don't want to be fussing around too much.

So, you've retired to this local area? You live just across the border?

I lived ten years at Boonoo Boonoo and five years ago I had to sell that up and I'm now south of Tenterfield.

So you like the Granite Belt area - the granite region?

Oh yeah. Boonoo Boonoo, I tripped over the place being up for sale and I loved it there.

It would be nice.

I had a great lot of that high altitude swamp on the place.

I can just imagine going for walks every day and seeing it.

It was lovely over there. My block linked basically with Bald Rock, across the Mt Lindsay Highway through to Basket Swamp National Park. Yeah, I loved it.

I just can't believe how quiet it is around here.

Clean air...

Let's see if I've got any more questions for you... Oh, the last one is, you mentioned you know some botanists from the University of New England?

Yeah. Ian Helford. He collected stuff here over the years. But he first collected here in '67.

Was this for his university?

No. Ian's an interesting person. He's actually 75 or 76 - in two week's time he's graduating with his PhD. And he hasn't had a degree.

Wow. So how did you meet him? Was it on the job?

Ian? No, well he was doing Forestry. He was a couple of years ahead of me. We met bushwalking. 1965, it would have been. We've had a friendship since then. He got a job with Canberra Botanic Gardens which has the National Herbarium. And he started working as a technician with the National Herbarium, collecting.

I noticed when I was looking at the [Queensland Herbarium's] records, that there are a lot shared with Canberra. So that was probably him.

I think he collected one undescribed species from a hill across from the Day-use Area... or something like that.

There are a lot of unique species around here.

Oh hey, it's amazing, you know. But this whole area, the Northern Tablelands, you know - down to Bolivia, out to Torrington, Girraween, Bald Rock, Boonoo Boonoo... It's a hot spot for Acacias, Homoranthus... Especially the species of Homoranthus, like around Tenterfield there, like every rock and hill has got a species for itself...

So, when you were doing your park planning, you'd take the species into account?

Well, that would be part of the value, the unique. You'd sort of approach it with two lines of thought. What I'd call special species - that's the endemics. They're your first priority, the endemics or "threatened". Then another one would be "type locality" for the collection. A lot of these things are on restricted little habitats, eh? Particularly the wetland... You know, the soggy, boggy areas. So a lot of things might be rare, but it doesn't necessarily mean they are threatened

It's just that they're small populations in a restricted area.

And they've always been like that. I've even found a Homoranthus on my place. There's been one record of it on Basket Swamp which is just a few kilometres over. And then we found another one at Carol's Creek, a little bit to the north. But those are just three. And there's probably only half a dozen plants over at Carol's Creek, there an area of about 600 square metres where they were growing on a swamp. Right on a water channel - a swamp. And likewise over at Basket Swamp. So whether you say are they threatened or not?

And were they the same species?

Yep. Well, at that stage it was undescribed. It has been described now. So, you know, those sorts of things, hey, that's of value.

Definitely. So when you are planning where the tracks go, do you avoid those areas?

Theoretically. But then, you don't always have that information.

That's true. There might be something new right next to the track that no one's noticed yet.

The Junction Track... I was here with Ian and Jeremy Bruhl, who's a botanical professor at the University. Jeremy's into sedges. We went down and there's just been one collection. Just off the track. We could have put the track through the middle of them. But there might be more around. It might be just that sort of thing, eh? You get a patch here, a patch there. There might be a lot of them.

I think that's about all my questions.

I can't think of much else, to be honest. (Laughs.)

Well, you've been absolutely brilliant and thank you very, very much for coming.

Paul Grimshaw, Trevor Vollbon and Tom Ryan. |

|