|

Lichens are a fascinating symbiosis between a fungus and one or more photosynthesising algae or, to a lesser extent, cyanobacteria. The partnership works well. The photobionts contribute to it by providing carbohydrates while the fungus gives the lichen its body and ensures protection against i.e. moisture loss and UV exposure. Lichens are named after the fungal partner. Given time, moisture and some light, lichens grow on almost any substrate, including man-made structures. In a natural environment they grow on soil, rocks, bark of trees, dead wood, and even leaves of rainforest vegetation.

Lichens are categorized according to their growth forms. They are aptly named fruticose when they have a shrubby appearance and can be hanging or grow upright. They can truly look like miniature shrubs with branches, attached to their substrate at one point only. These branches can resemble pendulous straps or have a cylindrical shape or even be hollow like the perforated pseudopodetia of Cladia retipora.

Fruticose lichens on bark. From left:

Usnea scabrida subsp. elegans, Stanthorpe; Teloschistes sieberianus, Toowoomba;

and Ramalina celastri, Indooroopilly.

They are called foliose when the thallus (lichen body) has a leaf-like and mostly flat appearance, grows in lobes, has a distinctive upper as well as lower surface (unlike its crustose counterpart), and is only loosely attached to the surface it grows on.

Foliose lichen: Flavoparmelia rutidota, Stanthorpe.

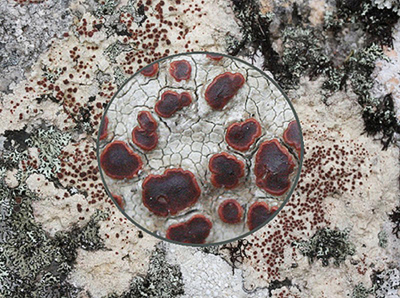

The thallus of crustose lichens is very thin and attached to the surface like a crust. Any removal of the lichen means taking parts of the substrate as well.

Ramboldia sanguinolenta

Ramboldia sanguinolenta, a crustose lichen on rock, Stanthorpe.

Squamulose lichens like Cladonia rigida have primary and secondary thalli. The primary thallus consists of minute scales from which fruticose podetia arise. Fruiting bodies can be found at the tip of fertile podetia.

Cladonia rigida

Cladonia rigida

Lichens generally reproduce vegetatively via soredia or isidia, two structures on the thallus surface consisting of fungal hyphae and algal cells. Both easily break off and disperse to new locations where they may start a new lichen. Isidia are tiny often cylindrical or pimple-like protuberances on the thallus surface. Soredia mostly have a powdery appearance or develop in clusters called soralia.

From left: Isidia on Leptogium sp., Indooroopilly; soralia on an unidentified lichen from Mt Nebo.

Only the fungal partner of a lichen can reproduce sexually. Most lichens are ascomycetous. Fungal fruiting bodies called apothecia come in a variety of shapes. They are often disc-like when emerging from the lichen thallus, but may also have an elongated form or may be positioned on the tips of podetias like different Cladia and Cladonia species. In some lichens, spores are produced in perithecia - flask-like fruiting bodies imbedded in the thallus and containing the ascospores.

From left: Glyphis cicatricosa on bark, Indooroopilly; ground lichens Cladonia floerkeana with bright red

apothecia, Chapel Hill; and Cladia retipora with fungal fruiting bodies at tip of pseudopodetia, Stanthorpe.

Lichen identification starts with the description of thallus structure, surface texture, and by distinguishing the reproductive methods. Thallus colour can be important but is unreliable as it varies with moisture content. Spot test are an important method. Very small amounts of chemicals are applied to the thallus. Any potential colour change in the affected area may give clues to the lichen's identity. This traditional method based on chemistry is relatively easy to apply but also limited. It has its improved continuation in the use of the more sophisticated thin layer chromatography where extracts of the lichen thallus are spotted onto a glass or aluminium plate and undergo a series of solvent and other treatments identifying their chemical components.

Lichens dry out easily, but are equally fast in reabsorbing water after rainfall or from the atmosphere. Photosynthesis is resumed without delay once the thallus rehydrates. (See Heterodea muelleri, below.)

Fungimap target species Heterodea muelleri,

a common ground lichen in open eucalypt forests of South East Queensland.

Lichens are pioneers. Their acids break down rocks and help the formation of soils. They are able to colonise areas bare of any vegetation by contributing to the creation of protective soil crusts.

Growth in lichens is slow compared to that of our trees, shrubs and flowering plants. It depends on the type of habitat, on climate, and, of course, on the type of lichen. Among the slowest growing lichens is Rhizocarpon geographicum developing in maritime Antarctica at a rate of 16mm per century.

It is obvious that lichens are hardy survivors. They are found in all habitats from hot deserts to Antarctica where they form the by far dominant terrestrial vegetation.

How our native animals use lichens needs to be further explored. We know of a range of invertebrates feeding on them, among them mites, moth larvae, snails and slugs. Others use them to disguise themselves by covering their body with fragments of lichens or have evolved to resemble lichens. Birds build nests with lichen fragments, and some of our small mammals are known to feed on lichens. Lichens are an important food source for the endangered Mahogany Glider in Northern Queensland.

The juvenile Spiny Leaf Insect Extatosoma tiaratum has the appearance of a foliose lichen.

|