|

|

Long before European settlement, the traditional custodians of this land lived, hunted and prospered in the Girraween area.

There is very little information recorded about these Aboriginal people, but it seems that the Wallangarra/Girraween district may have been a meeting place between a number of family groups or clans.

The Kambuwal, Jukambal, Kwiambal, Ngarabal, Bundjalung and Gidabal people are all known to have been in the area. They probably came together for trade, gift exchanges, marriages and ceremonial gatherings such as feasts and corroborees. Bora Rings and other ceremonial sites have been found in Ballandean, Girraween (Bald Rock Creek valley) and Maryland.

|

Aboriginal artefacts on display in the park's Visitor Information Center.

More artefacts...

|

|

The Wallangarra/Girraween district was most likely chosen because the woodlands of the Severn River system had a plentiful food and water supply that could support a larger population. There were three foods found in the area that were a particular favourite - possums, Sword Grass seed and the Swift Moths that swarm in April.

Girraween lay along an ancient trade route. Travellers from the west would pass through the district on their way to the eastern coastlands, where they would trade their spears and boomerangs for shields crafted from rainforest timbers by the Bundjalung people.

Girraween also lay on a pathway that ran between northern New South Wales and the Bunya Mountains in Queensland. People from the New England, south-east coastal Queensland, Wide Bay, Burnett, Dawson and Darling Downs districts would travel along this path to gather for the triennial Bunya Nut Festival.

The explorer, Allan Cunningham, was the first European known to enter the Girraween area. He reported that he saw Aborigines only five times during his journey to and from the present-day locations of Tamworth (NSW) and Warwick (Qld).

‘And they, he said, “suffered us for the moment to view them at a distance”.’

Relations between the Aboriginal people and the European settlers in the Girraween district are said to have been congenial. Even so, the Europeans appeared to have been fearful of possible attack. Holes were drilled in the wooden slabs of their huts, through which the settlers could shoot if they needed to defend themselves. Thankfully, none of the conflict which had happened elsewhere in the region (such as the massacres of Aboriginal people at Allora and Tenterfield) occurred in the Girraween district.

|

|

|

Bluff Rock near Tenterfield, site of the 1844 massacre.

More About the Massacre...

|

Introduced European diseases such as measles and chickenpox, however, were responsible for the death of many of the Aboriginal people in the area. Cattle and sheep drove away their traditional food sources of kangaroos and wallabies and the growing number of farms changed the nature of the land. Some Aborigines became trusted workers on these farms, but others chose to move away. Others, still, were taken away by the Europeans to live on missions.

|

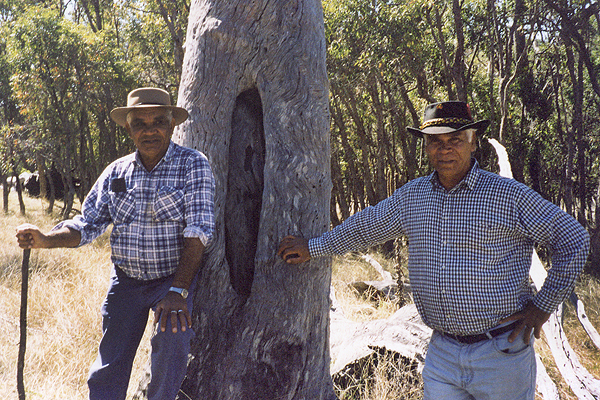

Kambuwal descendants with a marked tree.

|

|

Although their legends and place names have been lost to time, camping places, rock markings, tools and marked trees remain in Girraween National Park as evidence of the traditional custodians' life on the land.

Next...

European Settlers.

|

References

|

| 1. |

"They Came to a Plateau (The Stanthorpe Saga)"; by Jean Harslett and Mervyn Royle; Samuel Lee & Co. Pty Ltd, Stanthorpe; 1972; page 5.

|